In my time as a demand-side researcher, I’ve often been labelled as a highly technical researcher. This identification of me as technical comes largely from my ease and comfort in working with data and the many kinds of software that you can use to understand it, but it also comes from me being quite a purist in my view of how research should be conducted.

There is no step in the research process that brings out the purist in me more than that of sampling. I can often be heard drumming on about how your research is only as good as your sample. Yes, I’m a nerd – and I’m very happy to be one.

When I was a junior researcher, I was always drawn to studies that had bigger samples and what I saw as more robust or scientific sampling design. For me a probability sample was the definition of good research.

But I was also working for a commercial research house, and probability samples were a rare exception. They are expensive to run, and corporate research budgets often don’t allow for them. This meant I had to run many a quota-sampled study that I didn't quite believe in, and my preference was to always opt for the “compromise” approach – the geo-demographic sampling where the strict rules of probability sampling are relaxed to make the process cheaper but where starting points are selected using probability proportionate to size.

I was sceptical of the quota sampling approach because I saw too many quotas set with a pre-existing bias from marketers – a bias that suggested their users reflect the people whom they had defined in their target market. Sorry men who buy washing powder – you aren't in the target market we’ve decided on, so your opinions don't matter.

I have, more recently, come to appreciate the quota sample and realise that, when used correctly, it is sometimes the best way to sample. There is no better example of this than when conducting a mobile survey.

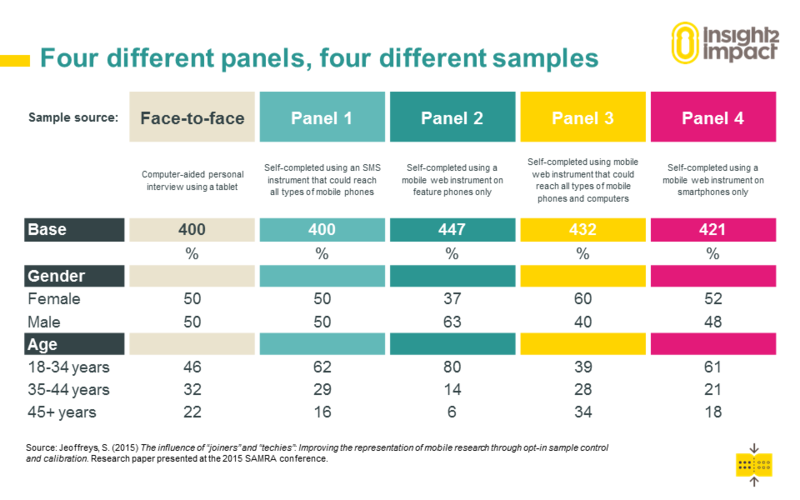

The reality is that when using a probability sampling method, your sample is only as good as the universe you’re drawing it from. For face-to-face interviews, this means representation of a nation or locality, but mobile sample sources do not necessarily include everyone. Mobile samples are, of course, limited to only those who have mobile phones. But most mobile samples have further constraints.

Currently the only way to ensure you have all possible mobile users in your sample source is to use a random-number generator to create your sample list. Theoretically this is sound, but in practice it makes mobile research as a sustainable form of data collection near impossible. This is because when you send out a survey invite to people for the first time, you can expect less than 2% of them to respond. This means that thousands of survey invites can go unanswered, driving up costs with very little return.

It is for this reason that mobile panels (a collection of people who have been recruited or have signed up to be surveyed) have been developed or are being developed. However, in these relatively early days of mobile panel research, I have not yet come across a truly representative panel. This means that currently a probability approach to sampling from the panel will result in the skews of the panel becoming skews in your sample. While this statement seems simple and probably obvious, I’ve seen many a seasoned researcher making this mistake because they are new to panel research.

It is essential for researchers to ask their mobile panel provider for two critical pieces of information:

- You need as much detail on the demographic profile of the panel as possible. This will help you to set quotas that both account for the skews in the panel and are realistic to achieve.

- You must get an understanding of how the panel is recruited. Panel recruitment can happen in multiple ways. For example, they can be recruited off lists from mobile network operators, recruited face to face, or through promotions.

If the panel is built from mobile networks, consider which networks are or aren’t included and whether this means something for the panel profile.

Be cautious of lists recruited from promotions. These can be attached to branded marketing activities, and a sample gained of users of a particular brand or category can have disastrous consequences for representation.

I can’t stress enough how important it is for researchers working with panels to get to know their sample source and (only once they’re familiar with the inner-workings of the panel) to then use quotas to avoid a disappointingly skewed sample.

This is Part 1 of a two-part blog on mobile sampling. Part 2 will consider the pros and cons of several different mobile sampling methods.